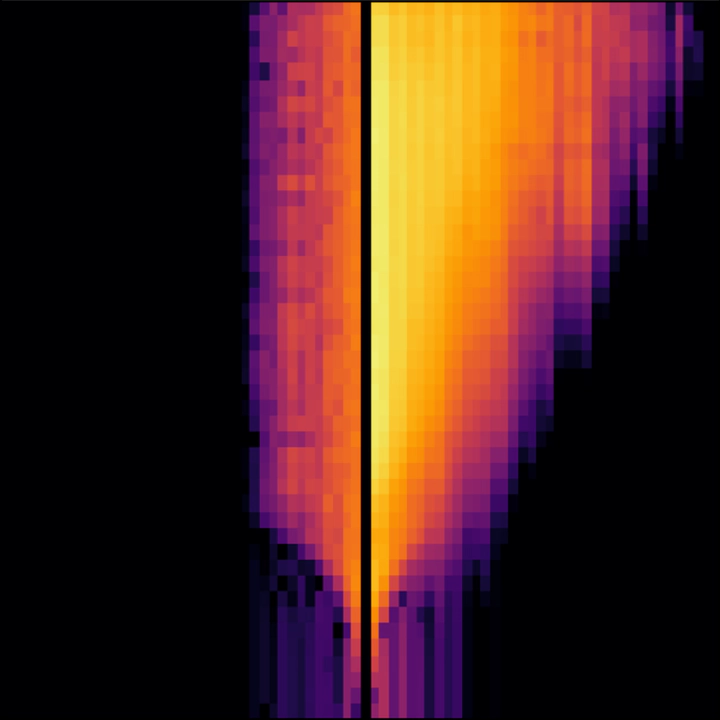

Unlike Anderson localized systems (left), in MBL systems (right), quantum correlations continues to spread in a logarithmic light cone. This can be visualized by the Out-of-Time-Ordered-Correlator, which was simulated for bosons in both $1D$ and $2D$, where the horizontal axis is space, and the vertical axis is log-time.

Unlike Anderson localized systems (left), in MBL systems (right), quantum correlations continues to spread in a logarithmic light cone. This can be visualized by the Out-of-Time-Ordered-Correlator, which was simulated for bosons in both $1D$ and $2D$, where the horizontal axis is space, and the vertical axis is log-time.

For the general public (click to open and close)

When we put espresso and milk together, we expect the two types of particles to mix, eventually resulting in a homogeneous mixture that we call latte. This phenomenon is called ‘thermalization’. In usual circumstances, we expect systems to thermalize, where a ‘system’ is simply a set of governing rules and agents. In our case of coffee and milk, the governing rules would be the physics of fluids, and the agents would be the coffee and milk particles.

There are also systems that do not thermalize. Non-interacting systems are a common example of non-thermalizing systems, since the individual particles cannot talk to each other and therefore cannot mix. One important non-interacting system is an ‘Anderson Localized’ (AL) one, where non-interacting particles are ‘localized’, i.e. they do not venture far away from their initial positions. In other words, they retain a memory of their initial states.

Naively, we expect that interacting systems to thermalize. What is somewhat unexpected, then, is that in certain situations, even interacting particles can stay localized and not thermalize. These are called ‘Many-Body Localized’ (MBL) systems and are a big part of condensed matter physics research today. Theorists usually study such phenomena on a lattice. A lattice is a simplification of space, so that instead of particles being in continuous positions, they occupy discrete ‘sites’, which are states that particles can be in.

In physics, there are two types of fundamental particles. The first are ‘fermions’, which are particles where only one particle can occupy a given site, much like the game of musical chairs. The second are ‘bosons’, where any number of particles can occupy a single site at a time. In the musical chairs analogy, it would be as if multiple players could sit on top of a single chair. Experimentalists have recently been studying MBL systems using bosons. However, both theoretically and computationally, bosons are much harder to solve compared to fermions. Why? Well, if you think about the possible states for fermions, there can either be a particle or no particle per site, so there are $2 \times 2 \times \cdots \times 2 = 2^L$ possible states, where $L$ is the number of sites. However, for bosons, if there are $N$ particles in total, there can be 0 to $N$ particles per site, so there are $(N+1)^L$ possible states. As you have more particles, there are simply more possible states for bosons compared to fermions.

In our work, we developed a way to study bosonic MBL systems efficiently. The method is quite abstract, but can be explained with the following analogy. A non-interacting quantum system can be thought of as a collection of pendulums, each located on a site in the lattice and each with their own frequency. Each pendulum only affects their own weights, each oscillating with their own frequency as they swing, without getting in the way of pendulums in other sites. In the roughest approximation, the interactions will only change the frequencies of these pendulums. This approximation is called ‘Poincaré-Lindstedt’ theory. By applying this theory/principle in our analyses of bosonic MBL systems, we found that even the most basic approximation is enough to show some of the hallmarks of MBL systems.

One of the hallmarks of MBL systems is the slow spreading of information due to the interactions of the particles. The above cover photo depicts a lattice. On the left is the non-interacting AL system, and on the right is the interacting MBL system. The x-axis is space, and the y-axis is ‘log-time’, where time increases exponentially as you go further up the graph, from 1 to 10 to 100 and so on. The areas where the lattice/graph is lit up indicates that information was transmitted. We can see that in the case of the AL system, the spread of information is stunted, but in the case of the MBL system, because the particles interact, information is transmitted, albeit very slowly, since you need to wait an exponentially longer time for information to spread to the next site.

If you’d like to know more about this work, please check out the PDF link, which links to the pdf at Physics Review B.

Abstract (click to open and close)

Recent experiments in quantum simulators have provided evidence for the Many-Body Localized (MBL) phase in 1D and 2D bosonic quantum matter. The theoretical study of such bosonic MBL, however, is a daunting task due to the unbounded nature of its Hilbert space. In this work, we introduce a method to compute the long-time real-time evolution of 1D and 2D bosonic systems in an MBL phase at strong disorder and weak interactions. We focus on local dynamical indicators that are able to distinguish an MBL phase from an Anderson localized phase. In particular, we consider the temporal fluctuations of local observables, the spatiotemporal behavior of two-time correlators and Out-Of-Time-Correlators (OTOCs). We show that these few-body observables can be computed with a computational effort that depends only polynomially on system size but is independent of the target time, by extending a recently proposed numerical method [Phys. Rev. B 99, 241114 (2019)] to mixed states and bosons. Our method also allows us to surrogate our numerical study with analytical considerations of the time-dependent behavior of the studied quantities.